Fact checking is NOT a pipeline

I work in automated fact checking: figuring out how to use technologies like AI and NLP to develop tools to support fact checkers. Over the last few years, I’ve read many papers and blog posts about the field and written one or two myself. Often, the scene is set by talking about the “fact checking pipeline”. This model breaks down the task of fact checking, as carried out by expert fact checking journalists, into a series of discrete steps with the aim of making the process easier to understand and potentially to automate. This is a laudable aim and the pipeline view is really useful for motivating research work at each stage.

But I’m increasingly convinced the fact checking pipeline is an oversimplification and that at some point, it will lead researchers up the wrong hill.

The pipeline

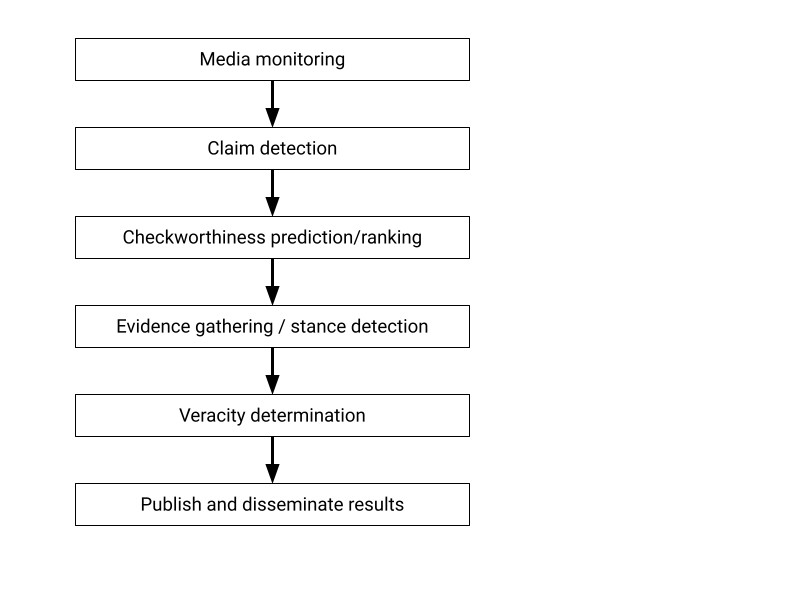

Here’s one version of the fact checking pipeline, which subsumes plenty of examples I’ve seen. (An appendix below lists some specific examples with references.)

|

From the top:

- We collect some media which we’ll assume is text (could be newspaper articles, FB posts, tweets, TV/radio transcripts, manifestos…).

- Then we find claims in the text, meaning statements about the world that are either true or false.

- Then we select or rank these claims for “checkworthiness” to prioritize which claims are actually worth spending time fact checking.

- Next is finding evidence related to the claim, from the web, Wikipedia, government data portals, private databases or wherever you trust. This may include deciding on the “stance” of a piece of evidence: does it support or contradict the claim?

- Then the big one: deciding whether the evidence shows that the claim is actually true or false (or partly true, or mostly false or some other category).

- And finally, publishing the result and encouraging people to read it.

Nice and simple!

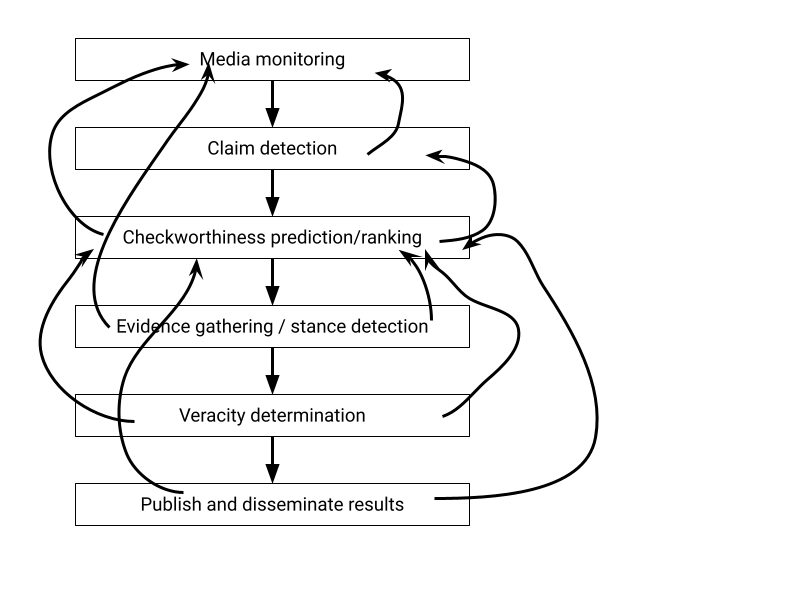

Missing arrows

As always, reality is more complicated than this simple model suggests. The temptation is to believe that by automating or scaling up one step, then the whole process gets a bit faster and a bit better. But I believe that many of these stages depend on each other, making automation harder (though not impossible).

For example, one critical factor in deciding if a claim should be checked is the availablity of evidence. If there is no evidence with which to test a claim, it can’t be tested. An experienced fact checker will often dismiss a claim as being not worth spending time checking because they know that suitable evidence is unavailable. So you can’t wait to gather evidence after deciding a claim is worth checking, or you may need to go back up the pipeline to revisit that decision.

Many versions of the pipeline I’ve seen omit the last step completely, seeing “publish” as a straightforward task that existing tools have already solved (email, blog posts, CMSs, etc). But fact checkers are journalists who want to tell stories that communicate complex issues to a broad audience. It’s not just a case of clicking “post”. Checkworthiness and explanations are both influenced by the nature of the audience: is this for the general public? For a specific community? For interested or motivated parties, who already have a lot of relevant knowledge? Knowing who the audience is for this particular fact check will influence whether it is worth checking at all, and perhaps what kind of evidence is required.

So if the explanation of why a claim is true or false is interesting, then that makes the claim itself more checkworthy. Conversely, if the evidence is trivial to retrieve and easy to interpret then it may not be worth the fact checker’s time to do anything: anyone reading the original claim can find the evidence themselves if they want to.

Trying to add these sorts of dependencies (and I’m sure there are plenty I’ve not thought of) to a pipeline leads to something a bit more messy, like the rest of life:

|

So as we continue to develop new automated fact checking tools, let’s not kid ourselves that we can just stick them end to end and solve everything. We’ll still need a way of coordinating the whole process, and perhaps that’s best left to the (human) experts.

Appendix

I’m not sure where the “fact checking pipeline” idea originates (please let me know your earliest sources!) but Lucas Graves (2017) said in an influential paper, “I divide fact-checking routines into five distinct areas…: choosing claims to check, contacting the speaker, tracing false claims, dealing with experts, and showing your work.” I’d suggest that contacting the speaker and dealing with experts are forms of evidence gathering, so it fits broadly into the pipeline model.

A slightly earlier paper by Andreas Vlachos Sebastian Riedel (2014) help spur early work on automated fact checking, but focussed on claim verification, while their 2015 paper introduces claim identification as well as verification.

The CheckThat! Lab at recent CLEF conferences (e.g. Atanasova et al, 2018) define a series of tasks that together form a similar pipeline: “First, the input document is analyzed to identify sentences containing check-worthy claims [task 1], then these claims are extracted and normalized, and finally they are fact-checked [task 2].” And that was the basis for the pipeline we described in a literature review I co-authored recently (Nakov et al, 2021).

These papers show the value of the pipeline model to motivate research into different aspects of automated fact checking, as long as we don’t forget the ultimate artificiality of the pipeline.

References

Atanasova, P., Barron-Cedeno, A., Elsayed, T., Suwaileh, R., Zaghouani, W., Kyuchukov, S., Martino, G. D. S., & Nakov, P. (2018). Overview of the CLEF-2018 CheckThat! Lab on Automatic Identification and Verification of Political Claims. Task 1: Check-Worthiness (arXiv:1808.05542). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/1808.05542

Graves, L. (2017). Anatomy of a Fact Check: Objective Practice and the Contested Epistemology of Fact Checking: Anatomy of a Fact Check. Communication, Culture & Critique, 10(3), 518–537. https://doi.org/10.1111/cccr.12163

Nakov, P., Corney, D., Hasanain, M., Alam, F., Elsayed, T., Barrón-Cedeño, A., Papotti, P., Shaar, S., & Martino, G. D. S. (2021). Automated Fact-Checking for Assisting Human Fact-Checkers (arXiv:2103.07769). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.07769

Vlachos, A., & Riedel, S. (2014). Fact checking: Task definition and dataset construction. Proceedings of the ACL 2014 Workshop on Language Technologies and Computational Social Science, 18–22.

Vlachos, A., & Riedel, S. (2015). Identification and Verification of Simple Claims about Statistical Properties. Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2596–2601. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/D15-1312