A small language model made from matchboxes

Over the last year or two, everyone has heard about “large language models” and their use in tools like ChatGPT. Well, I’m here to talk about small language models (SLMs) and one in particular that I’ve just built. I call it MESLaM, or Matchbox Educable Small Language Model1. MESLaM is a set of matchboxes, each labelled with a single word and each filled with little bits of paper. Each bit of paper has a single word printed on it. The set of words in each box was chosen to reflect the text of Green Eggs and Ham2 by Dr Seuss. And that’s it: no computer, no wires, no AI. And yet it can generate new text!

Let’s look at the model and what it can do.

First, here is a picture of MESLaM. MESLaM consists of just 35 plain matchboxes, each with a word written on the top and with a few slips of paper inside.

Below are some of the boxes opened to show their contents: slips of paper, each with a single word on them. As explained below, the words in the box can come immediately after the word written on the box.

|

The box green only contains the word ‘eggs’ over and over again. This is because in our text, the word “green” is always followed by the word “eggs”. |

|

<start> contains lots of different words, as the training sentences start with different words (though quite often, it’s “would” or “could”). |

|

The and box contains lots of “ham” but also “I”, “on”, “you” and others. The sequence “…and ham” occurs a lot in the training text. |

|

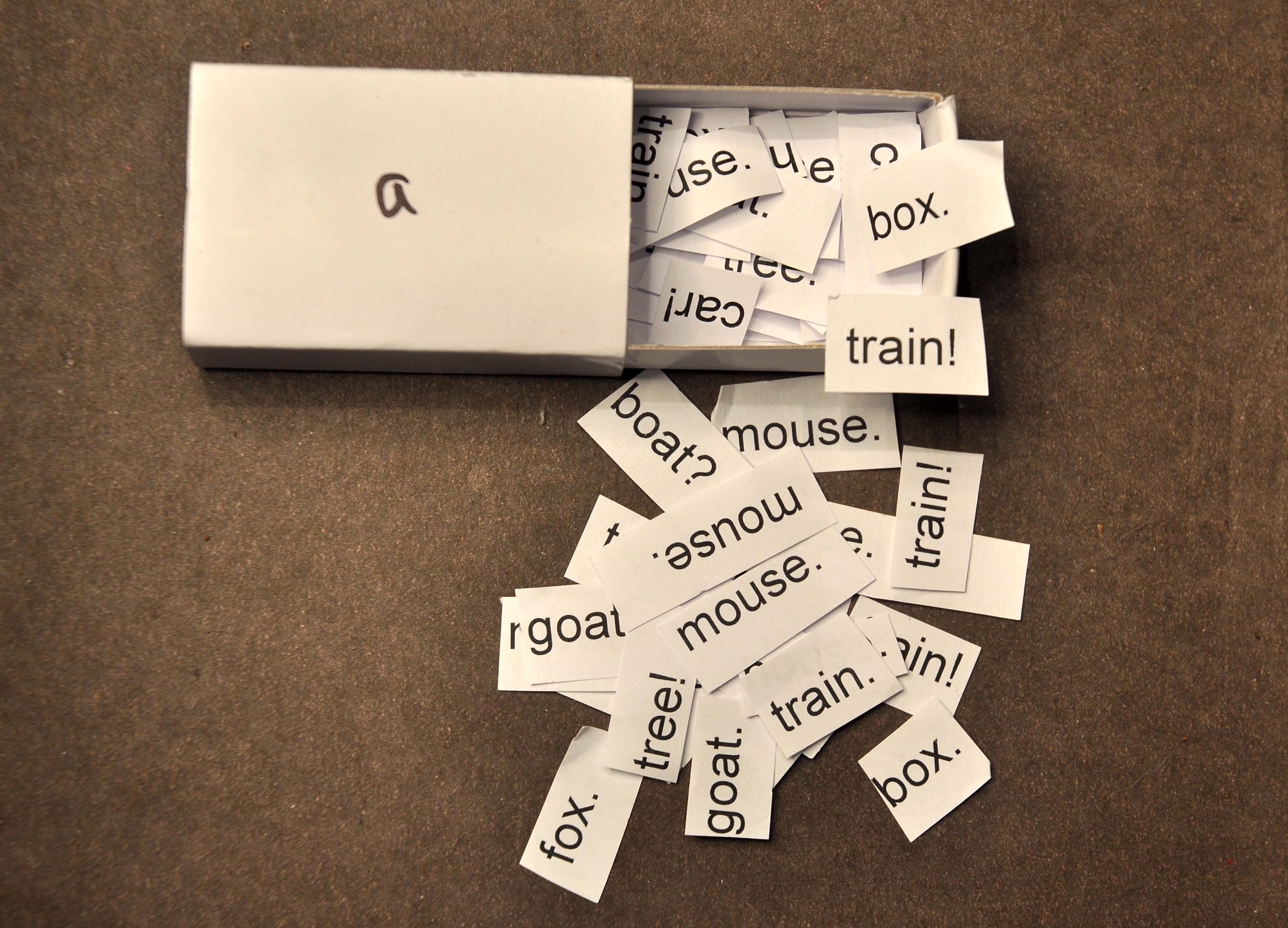

The word “a” is followed by lots of different nouns, including “mouse”, “train”, and “fox”, so they’re all in the a box, some multiple times. |

Generating text with MESLaM

One of the boxes is specially marked <start> and the slips of paper in this box show every word that can start a sentence, based on the training text. To generate a new sentence, we simply take a random slip of paper from this box and note the word. This is the first word of the new sentence. To generate each successive word, we open the box labelled with the current word and pick one slip at random and note the word. This continues until the new word has a terminating punctuation mark (i.e. a full-stop, exclamation mark or question mark).

Suppose the word drawn from the <start> box is “I”. This defines the first word of the sentence. We then open the box labelled I to see what words can follow it, and pick one slip at random. Suppose we pick a slip labelled “do”. That becomes the second word, and we need to open the do box to find what word can follow it. And so on. In the video below, the process continues until the slip labelled “tree.” is drawn from the box labelled a. The full-stop on the slip shows us it’s the end of the sentence, giving us:

I do not like them in a tree.

It’s not going to win a Geisel Award, but it is a proper sentence, it was written by MESLaM and it doesn’t appear anywhere in the training text. It’s generated novel text!

Here’s a video of MESLaM producing exactly that sentence. Note that when I filmed this, I genuinely didn’t know what sentence it was going to produce.

Each time we run the process, we’ll generate a new sentence driven by the random selections. Here’s another video when MESLaM generated the sentence “Could not like them anywhere.”.

And here’s a much longer sentence it created, “And I do so like them here they are so good, you may like them with a tree!”.

Perhaps not the most gripping prose style, but it’s definitely producing a variety of novel sentences, which is the aim.

Training the model

In a later post, I’ll explain the training process in plenty of detail (and an epic video!), but the outline is simple enough. The goal is fill each box with the words that can immediately follow the word written on top of the box. The more copies of a word that are in a box, the more likely that word is to be selected as the next word.

To train MESLaM, I split the text of Green Eggs and Ham into sentences. Taking each sentence in turn, the first word went into the <start> box. I also wrote this word on a new box, if there wasn’t already a box with that label. Then I took the next word in the sentence and put it into this box. So each box contains the words that come immediately after it, and each word goes into the box labelled with the word that comes before it. Simple? Perhaps an example would help. After training with the sentence:

“Would you, could you in the dark?”

the boxes look like this:

| Box label | Contents |

|---|---|

| <start> | would |

| would | you |

| you | could, in |

| could | you |

| in | the |

| the | dark? |

The box you contains two slips of paper, for “could” and “in” as both words follow immediately afer “you” in this sentence. Note that there is no box labelled “dark” because we haven’t seen any word follow “dark”. As shown in the photos above, every instance of the word “green” in our training data is followed by the word “eggs”; so the box green contains nothing but lots of copies of the word “eggs”.

Why did I do this?

My original motivation was my concern that some people were so overwhelmed by LLM chatbots that they genuinely believe they’re sentient. Plenty of others have claimed it is at least a signficant step towards artificial general intelligence - you know, proper AI. I wanted to demonstrate that generating text, even fluent text, does not require any sort of intelligence. So I wanted to build a text-generating model that is as transparent as possible, with nowhere for sentience to hide. Let me know if I succeeded.

Also, I am a massive nerd. Hello!

Extensions

The text that MESLaM produces is rather less impressive than ChatGPT and its competitors. How could it be made better?

First, MESLaM only uses a single word of context. As it generates new sentences, it only considers the current word as a guide to pick the next one. Modern LLMs have a context of hundreds or even thousands of words, which leads to greater coherence and relevance of responses. We could extend this by adding boxes with two (or more) words, whose contents define what can come next in the sequence. It’s the same idea, but would need a lot of boxes.

Second, MESLaM was trained on a single, short book of less than 800 words. LLMs are typically trained on billions of words from many thousands of books and websites, so can of course produce a much wider range of outputs. With enough time and boxes, we could keep training MESLaM as much as we wanted though.

And third, ChatGPT and other chatbots are not just language models: they are wrapped inside complex and proprietary tools that perform substantial (though largely secret) pre- and post-processing. For example, ChatGPT is designed to not produce racist or violent output. I assume that the inner model produces all sorts of offensive text but the wrapper recognises and removes it, and triggers the LLM to try again before anything is shown to the user. Thankfully, MESLaM’s training data is small enough for us to be certain that there’s nothing bad there.

So we’ve seen that even a small lanaguage model can generate novel text without any hint of sentience. I hope this goes some way to convincing people that large language models are also not intelligent, however impressive their outputs are.

-

The name is a large nod to Donald Michie’s MENACE, short for Matchbox Educable Noughts and Crosses Engine. He demonstrated that a set of matchboxes with coloured beads could learn how to play a decent game of noughts and crosses (tic-tac-toe). His main paper on it is from The Computer Journal, 1963 – yes, it’s 60 years old! – though the work predates the paper by a couple of years. So MENACE was built a year or so after Green Eggs and Ham was published, and AFAIK, a year before it was published in the UK (1962). ↩

-

The main reason for choosing “Green Eggs and Ham” is that it only has 50 different words. Each matchbox defines the words that can follow it, and quite a few words only appear at the end of a sentence, so we end up with 34 boxes, including the extra <start> box. ↩